2019 was the last year of PragPub, but you can now get the whole year in one handy bundle. A few highlights: David Smith on augmented reality, Eric Redmond on AI, Frances Buontempo on machine learning, Jack Woehr on quantum computing, Michael Nygard on coding elegance, Venkat Subramaniam on functional style, Woody Zuill on mob programming, James Grenning on TDD, Michael Feathers on groupthink, Michael Swaine on computer history, plus all the regular columnists. Available now from The Prose Garden.

Author: Michael Swaine

Michael Swaine was part of the launch team for the first personal computer newsweekly, InfoWorld. He co-authored Fire in the Valley, the seminal computer history book on which the movie Pirates of Silicon Valley was based. He was the long-time editor of Dr. Dobb’s Journal and of PragPub and has launched, written for, and edited numerous other magazines.

The Age of Mobility

Remember this one?

Embracing the future, Mike goes mobile, as long as his wrists hold out.

More mobility. Must have maximum mobility.

The yoga’s helping, and of course the finger-stretching exercises, but despite all my efforts, the smaller joints are still a tad tight.

The more one embraces mobility—in the form of mobile phones, portable computers, sub-notebook computers, in-car computers, personal digital assistants, MP3 players, pagers, beepers, and other forms of pocket, lap, wrist, head-mounted, strap-on, wrap-around, and surgically implanted technology, the more need one has for mobility—in the form of flexible fingers, willing wrists, and forgiving forearms.

We are tearing headlong into a mobile computing future while leaving our wrists behind, a tortuous image for a torturous technological trend, and that doesn’t even touch on the psychic trauma.

Jacqueline Landman Gay first tagged deja vu as a repetitive motion injury, but I’ll take credit for first identifying the syndrome of psychotechnological whiplash, caused by being rear-ended by rapidly advancing technology.

Mobile computing in its many forms is careening out of control around the cloverleafs (cloverleaves?) of the information superhighway, shaking up the PC and Web development industries like tourists in the Space Needle during Seattle’s recent quake, and provoking even more far-flung figures of speech than these.

Mobile computing calls into question the venerable concept of the desktop personal computer, a concept on which rests an uneasy multi-billion-dollar industry. It raises daunting questions for Web developers, mostly along the lines of: how can I possibly design a reasonable Web page for display on a cell phone? (It would be prudent for us not to dwell here overlong on the fact that the original concept of HTML was that all pages should be display-size independent; it’ll only make us feel bad.) Plus, it gets you in the joints.

Even the language of mobility tests the tendons, although that’s a tendency it shares with pre-post-PC technology. One just gets the PC acronyms memorized and now there’s a whole new set of mobile acronyms. HTML, make way for WML; and wrist get ready to wrap around WAP because acronyms, especially unfamiliar ones, twist the typing hands into painful poses.

Which I’m willing to put up with as part of the cost of the mobile experience. And boy do I want that mobile experience. I want to integrate my voice browsing and audio content aggregation with big honking alerts. I want roaming wireless access, instant connection with everything around me, I want BlueTooth on a BlackBerry. I want streaming video, streaming audio, streaming smells. Give me streaming pixels, unleash the streaming text.

I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade into your enfilade, cast your multidimensional browser spell my way, I promise to go multi-D. But do I go thence on Mike Rosen’s CubicEye browser, which displays five Web pages at a time on the inside walls of a virtual cube? Or do I ride the BroadPage browser, with its tabbed and tiled multi-pane views that let me juggle 100 Web pages at a time? Neither sounds like it would be much fun on a cell phone screen, though. I had a really twisted witticism to insert here about jugglers and flexible wrists, but my editor said it was too much of a stretch.

My desktop computer is a laptop, my LAN is wireless, my office roaming. I’m ripping my britches on the cusp of the curve, beyond the present reach of ergonomic design. And there’s the rub (on the heel of my left hand). The reams of recommendations on the proper position of the ergonomic desk, the shape of the ergonomic chair, the ergonomic posture, the ergonomic forearm angle, are all grist for the shredder when the computer sits on your lap. Time to revive the child-care books? Probably not; not everything that sits on your lap deserves to be treated like a child, just as not everything that sits on that rickety table on the plane deserves to be treated like a barf bag.

Airlines aren’t going to be much help regarding the proper ergonomic placement of that laptop in flight, either: these are the same people who think that it’s perfectly all right to attach the table you eat from to another passenger’s tilt-back seat.

Yet we do more and more of our work in moving vehicles. Trains, planes, and automobiles are the offices of the Twenty-first Century. The offices of Century 21, especially: no realtor really needs to go into an office any more, and other professions are becoming similarly mobilized.

As are we all. I can hardly wait until I get one of inventor Dean Kamen’s revolutionary gyroscopically-stabilized scooters that are going to end pollution and postal worker disgruntlement in our time. We’ll all soon be able to get mobile without Mobil—or Chevron or BP—but Dean, where am I going to put my laptop?

Reprinted from Dr. Dobb’s Journal.

Where I’m Blogging From

On our way to McGrew’s we make an impulsive left turn down Waldo Road.

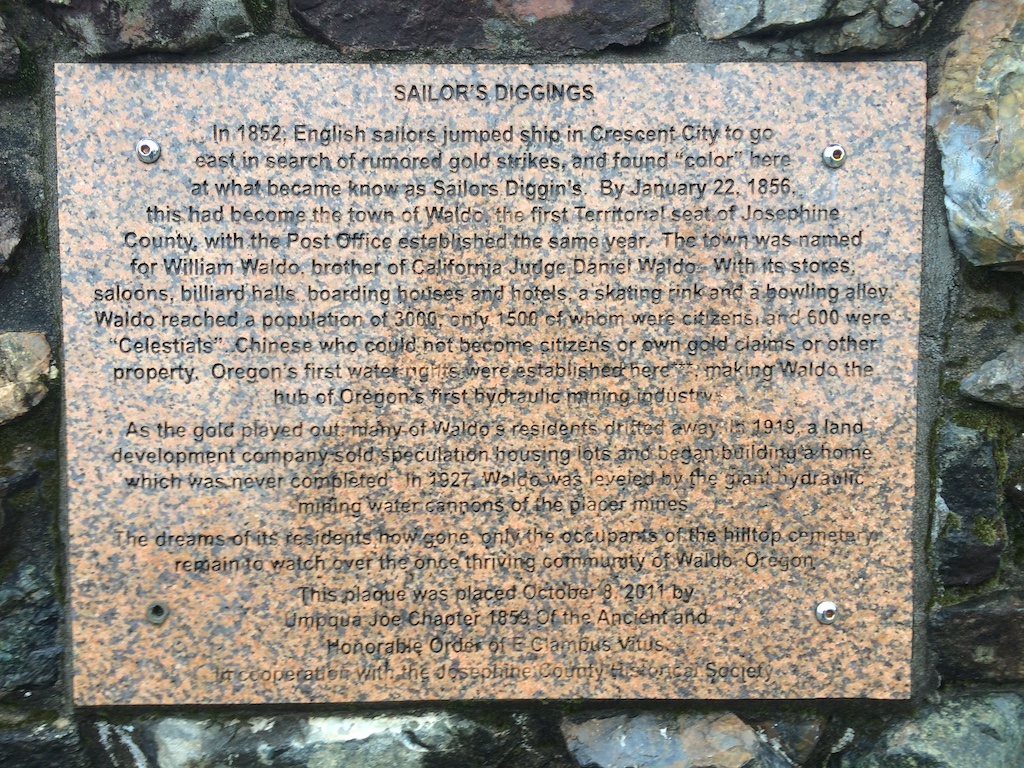

Winding through the woods, looking for crumbling buildings, we almost miss the plaque and the dirt patch just large enough for a car or two to pull off. We read the plaque, we hike up the hill to look around, but we find no trace of the abandoned town of Waldo. You can’t even call it a ghost town, it’s just a memory — and a plaque by the side of the road.

Where’s Waldo?

Oregon’s gold rush started here and in Jacksonville to the east. There are still abandoned mining tunnels under the buildings and streets of Jacksonville, which today is a bustling tourist destination, celebrating its gold-rush history. But there are no buildings or streets left to remind anyone of Waldo.

Waldo’s flame burned brightly and briefly. In the 1850s thousands of people came here seeking their fortune — and there was fortune aplenty to be dug out of the ground. Waldo prospered, and the whole region grew in population and began to be taken seriously. By the middle of the decade Waldo was picked to be the county seat of the newly-created county of Josephine. Oregon Territory was on its way to becoming a State, and the future glittered.

But in the early 20th Century the gold ran out and the town of Waldo faded away. It got bypassed by the Redwood Highway, the sole route connecting southwest Oregon with northern California. History and travelers ignored Waldo.

A Beer at McGrew’s

We return to the Redwood Highway and head south.

Back in the 1880s, you could take the stage down the Redwood Highway, through those California redwoods to the coastal town of Crescent City. Here, if you wanted to go farther south, you’d have to catch a ship bound for San Francisco. As late as the 1930s, when intrepid motorists were making the journey south, the highway, only passable in summer, reduced to one lane of dirt winding up switchbacks over Oregon Mountain.

A tunnel was blasted through the mountain in the 1960s, but even today the Redwood Highway just south of here snakes around outcrops along steep cliffs over river canyons and the speed limit drops to the teens.

Our destination is closer, only a mile ahead of us and five miles north of the California line: the town of O’brien, named for John O’brien, who settled here in 1899.

By weekly tradition we drink a beer at McGrew’s every Sunday afternoon and review our achievement for the week and plan for the coming week.

On this side of the highway, McGrew’s restaurant and bar is it: the only business and almost the only building in O’brien. Across the highway the downtown has more to flaunt: a Post Office, country store, gas station, U-Haul drop-off, and take-out taco shop, though most of them are in the one building. The original Post Office was a log cabin, moved here from Waldo when the town was dismantled.

Other O’brien attractions include a train caboose, an antique police car, and a giant fly sculpture on top of the restrooms, all saying “Welcome to Oregon!” to travelers heading north.

Head north we do, back to our riverside home, seven miles up the Redwood Highway.

Your River Flows Backward!

That summer as we hung out on our Illinois River beach with visiting friends, the river was so calm you could only tell it flowed by looking up or downstream where the shallows broke and bubbled the water. Our friend Bill stared at the rapids and turned to me.

“Your river’s flowing the wrong direction!”

He’d realized that the river was flowing inland. That seemed wrong to him. Shouldn’t rivers near the coast flow toward the ocean?

Bill was right, it is a little odd. Our Illinois Valley is defined by this river flowing inland down out of the Coastal mountains of Oregon and California, and life in Southwest Oregon is bounded by these rugged mountain ranges that dictate how its rivers can flow.

Past our beach, the Illinois picks up speed to flow into deep wilderness with class 5 rapids, joining the Rogue before bending back finally to head for the coast. Our little spot on the river is truly mellow, though, at least until the winter rains come.

(I found some of the historical information here in Historical Images of the Illinois Valley — 1870s to the Present by Dennis Strayer, and Josephine County: the Golden Beginnings by Edith Decker.)