On our way to McGrew’s we make an impulsive left turn down Waldo Road.

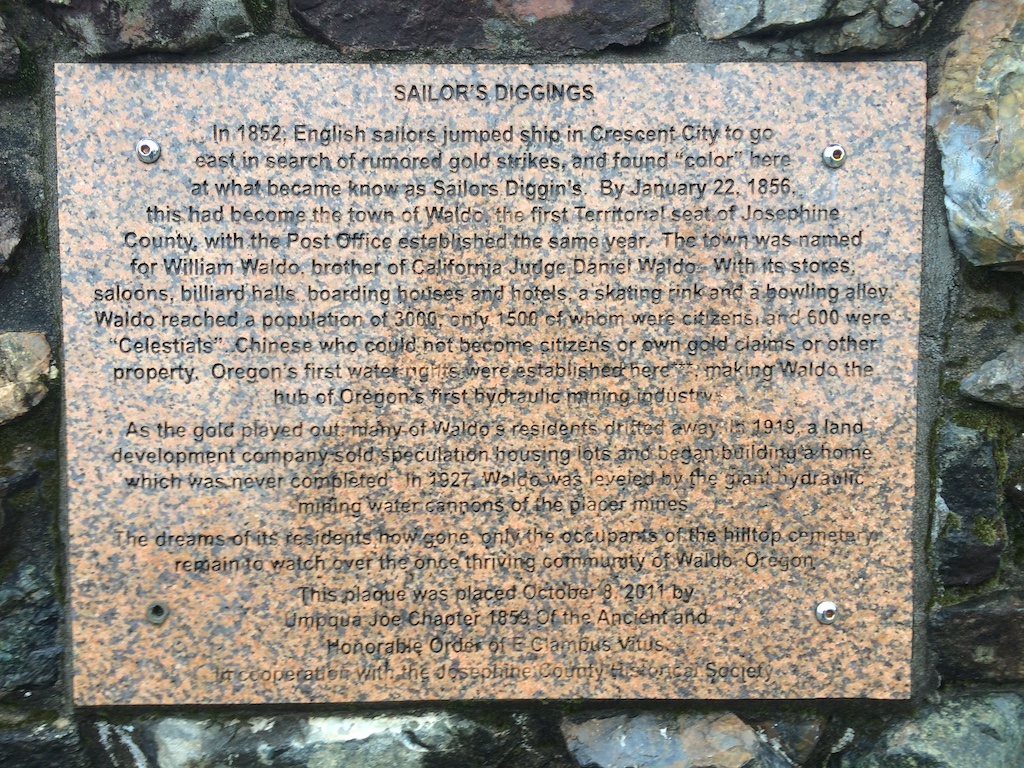

Winding through the woods, looking for crumbling buildings, we almost miss the plaque and the dirt patch just large enough for a car or two to pull off. We read the plaque, we hike up the hill to look around, but we find no trace of the abandoned town of Waldo. You can’t even call it a ghost town, it’s just a memory — and a plaque by the side of the road.

Where’s Waldo?

Oregon’s gold rush started here and in Jacksonville to the east. There are still abandoned mining tunnels under the buildings and streets of Jacksonville, which today is a bustling tourist destination, celebrating its gold-rush history. But there are no buildings or streets left to remind anyone of Waldo.

Waldo’s flame burned brightly and briefly. In the 1850s thousands of people came here seeking their fortune — and there was fortune aplenty to be dug out of the ground. Waldo prospered, and the whole region grew in population and began to be taken seriously. By the middle of the decade Waldo was picked to be the county seat of the newly-created county of Josephine. Oregon Territory was on its way to becoming a State, and the future glittered.

But in the early 20th Century the gold ran out and the town of Waldo faded away. It got bypassed by the Redwood Highway, the sole route connecting southwest Oregon with northern California. History and travelers ignored Waldo.

A Beer at McGrew’s

We return to the Redwood Highway and head south.

Back in the 1880s, you could take the stage down the Redwood Highway, through those California redwoods to the coastal town of Crescent City. Here, if you wanted to go farther south, you’d have to catch a ship bound for San Francisco. As late as the 1930s, when intrepid motorists were making the journey south, the highway, only passable in summer, reduced to one lane of dirt winding up switchbacks over Oregon Mountain.

A tunnel was blasted through the mountain in the 1960s, but even today the Redwood Highway just south of here snakes around outcrops along steep cliffs over river canyons and the speed limit drops to the teens.

Our destination is closer, only a mile ahead of us and five miles north of the California line: the town of O’brien, named for John O’brien, who settled here in 1899.

By weekly tradition we drink a beer at McGrew’s every Sunday afternoon and review our achievement for the week and plan for the coming week.

On this side of the highway, McGrew’s restaurant and bar is it: the only business and almost the only building in O’brien. Across the highway the downtown has more to flaunt: a Post Office, country store, gas station, U-Haul drop-off, and take-out taco shop, though most of them are in the one building. The original Post Office was a log cabin, moved here from Waldo when the town was dismantled.

Other O’brien attractions include a train caboose, an antique police car, and a giant fly sculpture on top of the restrooms, all saying “Welcome to Oregon!” to travelers heading north.

Head north we do, back to our riverside home, seven miles up the Redwood Highway.

Your River Flows Backward!

That summer as we hung out on our Illinois River beach with visiting friends, the river was so calm you could only tell it flowed by looking up or downstream where the shallows broke and bubbled the water. Our friend Bill stared at the rapids and turned to me.

“Your river’s flowing the wrong direction!”

He’d realized that the river was flowing inland. That seemed wrong to him. Shouldn’t rivers near the coast flow toward the ocean?

Bill was right, it is a little odd. Our Illinois Valley is defined by this river flowing inland down out of the Coastal mountains of Oregon and California, and life in Southwest Oregon is bounded by these rugged mountain ranges that dictate how its rivers can flow.

Past our beach, the Illinois picks up speed to flow into deep wilderness with class 5 rapids, joining the Rogue before bending back finally to head for the coast. Our little spot on the river is truly mellow, though, at least until the winter rains come.

(I found some of the historical information here in Historical Images of the Illinois Valley — 1870s to the Present by Dennis Strayer, and Josephine County: the Golden Beginnings by Edith Decker.)